News & Trends

“The phase of US hegemony is coming to an end.”

The two renowned investment experts Felix Zulauf and Dr Heinz-Werner Rapp are advisory members of the Globalance Investment Committee. They will answer our questions.

Inflation persists in the US and Europe. How do you think this will develop further, have we reached peak figures? Or is there a threat of stagflation? How will consumers in our country feel the impact of this inflationary trend?

Rapp:

First of all, when it comes to inflation, it is very important to prevent political mythmaking, which is unfortunately being accepted indiscriminately in many cases at the moment. The current inflation dynamics with price increases of over 8% would not be conceivable without the central banks’ previous unrestrained monetary inflation. In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic especially, the major central banks printed massive amounts of new money hand in hand with their governments to finance rampant government spending with the creation of money. These measures had a huge impact in 2020/21 and are the cause of today’s inflation. But many prefer to speakof the Ukraine war as a driver of inflation.

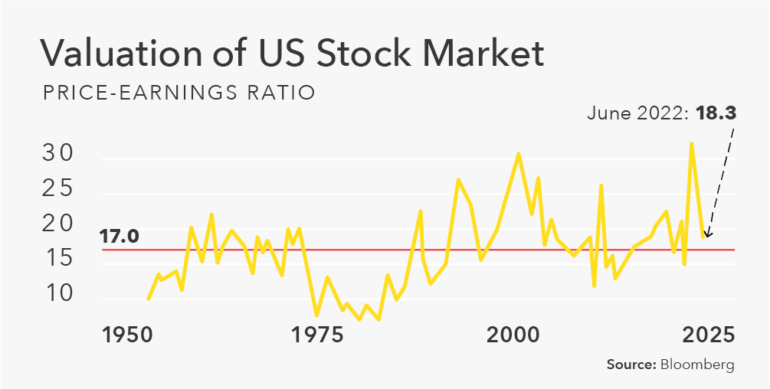

Unfortunately though, many different factors are now actually working towards rising inflation, including the effect of sharply rising energy and food prices triggered by Russia (hashtag wheat from Ukraine). With the global economy now also steadily weakening, exacerbated by the central banks’ turnaround on interest rates, we are indeed moving into an increasingly stagflationary scenario. This fact is now also being increasingly priced into the capital markets and is the reason for the sharp corrections in the first half of 2022.

Consumers are also feeling the pressure when they suddenly have to accept double-digit price increases at the petrol station, when shopping or on holiday. This point will undoubtedly put additional pressure on the economic development in the current year.

Zulauf:

We have a structural scarcity in the supply of essential commodities, in particular energy and food. It is the result of underinvestment due to the previous bear market that lasted over ten years. Policy has reinforced this with the move away from fossil fuels. We cannot satisfy the increasingly high-tech world’s hunger for energy just with solar and wind power. And because some nuclear power plants were shut down before alternatives were available in Europe in particular, we now have a bottleneck that will last for years. Added to this are the sanctions against Russia for political reasons, which is accentuating the scarcity even more.

Inflation rates will drop slightly from the current levels this year, but only if the demand for energy and grain is consciously curbed, as the supply will remain limited for years. This means that a recession is needed and the central banks must dampen aggregate demand with a restrictive monetary policy.

Higher energy prices are factored into virtually every consumer good and service. We now have the highest inflation in 40 years and private household incomes are negative in real terms, which weakens purchasing power, and probably will do so for several years.

Global central banks are in a tight spot, but how far can interest rates effectively rise? What impact do you expect on the capital markets with a view to the next quarters or next few years?

Rapp:

A distinction must be made with this question, because not every central bank will act in the same way. The US Fed – and the Bank of England, for that matter – seems determined to actually raise interest rates sharply as a weapon against the rampant spectre of inflation. For the US, this means that money market rates must move towards 4%. A recession is increasingly being accepted as collateral damage, so to speak.

A central bank that is acting purely “politically” like the ECB, on the other hand, will take much less action. Due to rapidly increasing tensions in the European Monetary System, we will only see the ECB take very limited interest rate steps in the near future; despite record-breaking and increasingly anti-social inflation trends.

This environment with a global turnaround on interest rates during an already weak economy is of course a toxic cocktail for the capital markets. That is why the global stock and bond markets have plummeted so massively since the beginning of the year. The more this image of stagflation takes hold, and unfortunately there are currently signs of this, the more uncomfortable it will become for the markets.

After many years of low inflation, the new environment is now bringing a tectonic shift for the capital markets, the effects of which will still be very noticeable in five years’ time.

Zulauf:

The price for money has been far too low for years, even after the recent interest rate hikes. But what is more crucial from my point of view is the quantity of money in the credit system, where we are already seeing a significant tightening of liquidity in the US. The reduction of the Fed’s balance sheet by $ 47.5 billion per month from June and double that from September is a massive drain on liquidity from the credit system and is cutting the blood supply to global financial markets.

Only the ECB is refusing to face the reality of more than 8% inflation as it raised the interest rate by a ridiculous 0.25% to still negative interest rates in July; and might perhaps increase it by just another 0.5% into slightly positive territory in September. This has nothing to do with monetary policy but a lot with dragging out state bankruptcies. Since Draghi, today’s ECB has subscribed to the Italian-French philosophy of demonetization – the antithesis of the old Bundesbank policy, which guaranteed a stable monetary value.

If a central bank does not apply the brakes, then the bond markets will. Yields in this segment are now at their highest level in eight years and the more the ECB drags its heels, the more the yields rise. The ECB knows nothing about economics and nothing about financial markets; it is a political bureau that is leading Europe into economic decline.

A trend towards the deglobalisation of the world economy is emerging as a result of the pandemic. How far will this development go? Who are the winners and who are the losers? What does this mean for the investment strategy?

Zulauf:

The international division of labour, i.e. that everyone does what they can do best and cheapest, is highly efficient and leads to increased productivity and rising prosperity. However, dependencies must never become too great, especially in an environment where different systems are hostile towards each other. So if the Western pharmaceutical industry purchases 80% of its active ingredients from China, then, to exaggerate, we can no longer even produce headache tablets without China’s help.

Therefore, such dependencies will now be reduced with parallel supply chains in many industries. This is particularly true for sectors that are strategically important, such as semiconductors, but also robots, pharmaceuticals, etc.

The global economy will continue to exist, but the degree of interdependence will automatically decrease because supply chain security is becoming more important than prices. This is an additional element to increase the price of various products, which drives inflation higher.

For the investment strategy, this all means much more defensive positioning in order to protect capital in this difficult environment. Interest rates will continue to rise until the markets start pricing in a recession. If, in a weak economic situation, the central banks then change course and stimulate the economy again, as they have always done, commodity and share prices may rise again for a few quarters, but no longer. Because then we would grow into double-digit inflation with much higher interest rates, which would eventually lead to a deep recession and much lower asset valuations. In particular, the global real estate market that is sensitive to interest rate changes would then also be hit, intensifying the crisis.

Rapp:

The COVID-19 pandemic was merely a visible amplifier of pre-existing trends that are more in the realm of geopolitics. We recently published a detailed analysis that outlines the prospect of a geo-economic turning point. Besides the Ukraine war, the strategic conflict between the US and China is also behind this. This conflict already has many front lines and is likely to intensify in the coming years. We therefore expect the global economy to increasingly sever links in many sectors, resulting in a progressive trend towards deglobalisation.

In an intensified form, this development could also materialise as a new version of the Cold War. In fact, this means a split of the world economy into two separate power blocs or hemispheres – a scenario also known as “bifurcation”. Global economic procedures, supply chains and transaction networks, but also capital flows and technology transfers would run differently in the future depending on the hemisphere they belong to , either “China & satellites” or the “US & the West”.

As a result, companies with a global footprint would then have a real problem continuing to operate globally. Considering that many companies today do a huge amount of business in China, the risk dimension becomes instantly clear. Long-time winners of globalisation could quickly become losers in such an environment. This kind of “geopolitical risk factor” will have to be considered more in future when analysing companies.

Relative winners in a bifurcation environment could mainly be those companies that are well positioned in their “own” hemisphere, but at the same time don’t have a cluster risk in the “other” hemisphere. One promising approach for the investment strategy in the future would then be a targeted selection of leading “single hemisphere players”, instead of a globally positioned equity portfolio.

How do you assess the increasing polarisation in the West and East? Are we in a period of great historic transformation? What are the implications of these developments?

Rapp:

With the war in Ukraine, the topic of geopolitics has, surprisingly for many, returned with great force. It is in fact noticeable that the world is in the midst of a historic transformation. The long phase of US hegemony (“Pax Americana”), under whose protective umbrella the past episode of intensive globalisation became possible in the first place, is coming to an end. Self-confident players like Russia and China, rising powers like India, but also smaller regional powers like Turkey are no longer willing to accept the global dominance of the US. Resulting accordingly in an increase in geopolitical upheavals, open confrontations, rifts and real military conflicts, as seen recently. So we are definitely experiencing a turning point – towards a new geopolitical “disorder”. The new scenario is characterised by increasing rivalries and intensified conflicts between the superpowers. This also has direct consequences for entrepreneurs and investors: the world is becoming more uncertain, developments less predictable and the economic world much more fragile. There is also the aspect of the world economy possibly splitting into competing hemispheres, the previously mentioned “bifurcation”. For many companies, but also for investors, this change in regime means a tough turning point, the significance of which is not yet understood everywhere though. Investors would be well advised to consider geopolitics as a separate risk factor as part of their investment strategy in the future.

Zulauf:

After the fall of the Wall, everyone thought that eternal peace had broken out. Hopes that China would move towards democracy through world trade have been dashed. The conflict between the hegemon (US) and the new upstart (China), already described by Thucydides 2,500 years ago, will intensify. The question about Taiwan remains unresolved and is a potential source of danger. Iran’s ability to build nuclear weapons also shifts the balance in the Middle East, where a proxy war is already raging. The Strait of Hormuz, through which 21 million barrels of oil are shipped daily, could one day be deliberately closed as blackmail.

Two blocs will probably emerge that are in conflict with each other. The democratic West led by the US and some autocratic states led by China. Many will move independently as opportunists in between, depending on the world situation and their particular interests. We are in for some very turbulent years with the risk of more military escalations.

Europe is completely unprepared, reliant on energy from Russia or the Middle East, while the US is self-sufficient and China has secured energy in the Middle East and Russia. No country in Europe can defend itself because we have dismantled our armies to the point of absurdity, let them go downhill and become pacifists. In other words: Europe is the least prepared region for these turbulent times.

Every cloud has a silver lining. Where do you see the greatest investment options and opportunities for the future?

Zulauf:

As long as the authorities (have to) put the brakes on economic policy, the risks on the capital markets will remain greater than the opportunities. As soon as there is a major economic downturn and the share indices are correspondingly lower, I expect the central banks to do a U-turn and pursue a policy of easy money again. If this is true, then assets that are in short supply will rise in particular, i.e. commodities such as oil, gas, grain, etc. This would trigger the next surge in inflation and push up yields on fixed income, which would then trigger an even bigger recession after a certain period of time has elapsed. Until this happens though, equities would also rise again with the injection of liquidity, especially sectors such as energy, commodities, defence and also hard-hit industrial stocks that would recover again after a massive valuation correction.

I expect a major roller coaster ride on the stock markets over the next few years and am increasingly leaning towards gold investments, which can provide balance in a portfolio given the increasing systemic instability. There are some eventful years ahead with big ups and downs on the financial markets, but with very modest returns on average measured against the share indices. There are likely to be ever greater differences in the performance of sectors and individual stocks, as the increasing economic challenges will progressively separate the wheat from the chaff. Quality will prevail in the long term. The selection of individual securities is becoming increasingly important, but so is the timing of the ups and downs.

Rapp:

The war in Ukraine has once again thrown a spotlight on the entire commodity and energy complex. But this sector was attractive even before that, not least because of the new inflationary scenario. Commodities and gold perform relatively well in inflationary phases, which will continue to provide a tailwind for the sector in the near future.

At the same time, technology stocks are currently being sold off massively, triggered by the US Federal Reserve’s hard turnaround on interest rates. In many cases, this is happening in a rather undifferentiated manner, i.e. without taking individual valuations or business models into account. The reason is usually that entire sectors on the market are being sold “en masse” through ETF vehicles. As soon as the selling pressure has subsided, very attractive opportunities should present themselves again here for active investors and stock pickers. As global megatrends such as digitalisation, AI or cyber security will continue to develop very dynamically; after a correction, the corresponding stocks should again be included in the long-term calculations.

A year ago, China would probably have been mentioned here as a strategic opportunity. However, this prospect has been massively dampened – also from a very fundamental point of view. China is clearly increasingly distancing itself from Western principles, which entails high investment risks in the long run. Nevertheless, there are still opportunities there, for example in specific advanced technology segments; but this requires an extremely selective investment approach.

Dr. Heinz-Werner Rapp

Director and Chief Investment Officer of FERI Investment Research

Felix Zulauf

International Financial Expert, Zulauf Asset Management