News & Trends

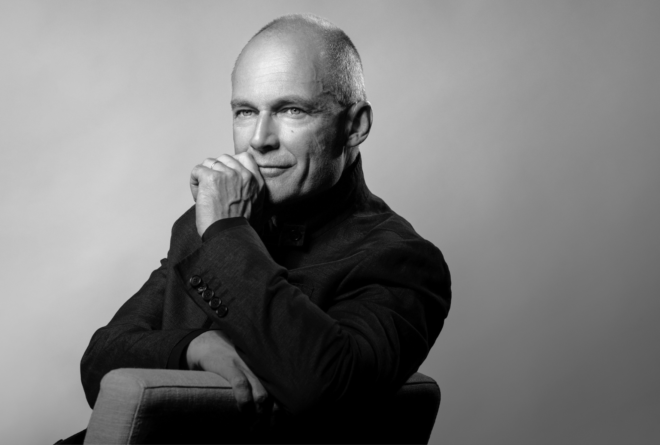

“Building an Efficient World” – Interview with Bertrand Piccard

The Swiss explorer and founder of the Solar Impulse Foundation Bertrand Piccard was the first to fly around the world in a solar plane. He is the father of three daughters, UN Special Envoy, Special Advisor to the European Commission and author of various books. He answers our questions.

The interview as a podcast for when you’re on the road. Enjoy listening!

Read the interview in full.

The Solar Impulse project designed a solar-powered airplane capable of circumnavigating the earth, overcoming the enormous challenge of generating the required power without fossil fuels. Has this experience shaped your views on the current energy crisis?

It’s a fitting comparison. When I initiated the Solar Impulse project, aviation experts told me it was impossible, because the sun would not provide enough energy to fly day and night. And this is the paradigm of our world. It is always about production: If we cannot produce enough, it won’t work. But it should be the opposite. If we don’t have enough production, we should save, consume less by being more efficient instead of producing more. And that is what we did with Solar Impulse. We coped with the energy the sun provided by designing a plane that was efficient. When we look at the war in Ukraine, what do we see? Less gas, less oil coming from Russia, and everybody’s first reaction is to desperately try to find another supplier instead of saying: Let’s be efficient, let’s save, let’s stop wasting energy with outdated and inefficient infrastructure. The food crisis is the same. Half the food produced worldwide is lost between production and consumption. Our world is a world of waste. That is the problem, not just for the environment but also for the economy.

In other words, we would have enough supply if we were more efficient and the technologies to be more efficient already exist?

Yes. We waste three quarters of the energy we produce simply because our systems are inefficient. Thermal engines have an efficiency of 27%. The Solar Impulse electric engines were at 97%. And it’s the same everywhere. Heating systems are a disaster. Incandescent light bulbs are at 5% efficiency compared to new LED lamps at 95%. We don’t need to sacrifice economic growth or our quality of life. If we replace and modernise all our infrastructure, the production we have today is more than sufficient, too much even. We could reduce consumption, which is good for the environment but also for profit margins. The increase in efficiency would pay for the upfront investment. In economic terms, instead of having a GDP that is coupled with the quantity of consumption, we would have a GDP coupled with the quality of efficiency. Protecting the environment is a new business opportunity.

The Solar Impulse foundation seems to have turned into a broad movement. Could you talk about the foundation’s goals and the projects you support?

The first Solar Impulse project was to circumnavigate the globe in a solar-powered airplane to prove that new technologies and clean energy could achieve impossible goals. Achieving this gave us credibility and influence. Our second challenge was to identify more than a thousand economically profitable solutions to protect the environment. Fortunately, everyone told me it was impossible at first. I liked that because when you face an impossible challenge, the people who join you are pioneers excited by the challenge, skilled people who come with all their talents and potential and say ‘we’re going to make it happen’. And that’s exactly what happened. In April 2021, we reached our goal of one thousand solutions. Today, we’re at 1,404. Our group of 370 experts assess these solutions. If they’re profitable and ecological, they receive the Solar Impulse efficient solution label. Our goal now is to promote the solutions, and take them to governments, heads of states, regions, cities and corporations. We’ve proven the solutions exist – now we need to implement them at every level.

I spoke to an entrepreneur who is part of your programme. He told me the label has made it easier for him to attract employees.

It’s an advantage I wasn’t aware of. So far, I’ve mainly heard innovators saying the label gives them more credibility with investors and customers, that it helps with marketing. I’m very happy to hear that. Our goal is to be useful to all these innovators and to be useful to the world.

The programme encompasses different sectors. From your perspective, which sectors have low-hanging fruit? Where are we technologically ready to move quickly?

I would say energy and construction. People don’t understand that new construction can be energy neutral and carbon neutral. You can have almost CO2-free cement, can make concrete out of demolition waste, have insulation that makes the building energy neutral. Heat pumps use three to four times less energy than a conventional heating or cooling system. This is something we need to do immediately. If you want to house the 2.5 billion people that are going to live in cities by 2050, you need to build a city the size of Manhattan every four months. It’s unbelievable, but true. If you build inefficiently, with bad insulation and outdated heating systems, you are locked in for 50 years.

The other topic is energy. You often hear that we will never be able to cover our energy needs with renewable energy, but if you put energy-efficient systems in place, you absolutely can. Solar energy is the cheapest energy in the world today, but it’s not only solar energy and wind, it’s also biomass, hydroelectricity and geothermal energy. You can put little water turbines in rivers without a dam or store heat with geothermic wells. All these things aren’t just nearly carbon neutral, they’re also new business opportunities.

Could you name two or three projects that you think have a lot of potential?

Celsius Energy drills ten holes at an angle in cities and connects heat pumps. Not for individual houses but for huge buildings. It reduces the energy bill to a third of what it was originally, which pays for the upfront investment. Another example is a project that collects unrecyclable household waste and turns it into building bricks or gravel. A third project is that from Eco-Tech Ceram. I like it because it’s not high-tech, it’s common sense. They recover and harness the heat from factory chimneys. That leads to a 20-40% reduction in the factory’s energy bill as well as less CO2 in the atmosphere.

There’s no silver bullet, no one solution that’s going to change the world. But the miracle is that there are so many solutions. It’s what I like to call the piranha theory. If one piranha bites you, you hardly feel it. But if 1,404 piranhas attack you at once, you’re a skeleton within three minutes. And this is what we have to aim for with all these solutions. Each solution bites off a little bit of pollution, a little bit of CO2, and in the end you have a modern, efficient and clean world.

Our world appears to be at a turning point. Geopolitical conflicts, war, a difficult economic situation. How do you think that will impact the companies in the foundation?

It will negatively impact short-minded people who want to keep going as before, fighting for oil and gas, and so on. But for the people at the foundation, it’s a great incentive because the price of fossil fuel is going up and you have less supply, so it’s a fantastic opportunity for energy efficiency and renewable energies. Of course, we also have to open people’s minds and show them, look, instead of crying because you don’t have enough Russian gas, start smiling because you have solutions that are much cheaper. But you need to act. If you want to have more hydroelectricity in Switzerland for example, you need to add several metres to the dams. And you cannot afford to have green parties or nature conservationists prevent the dams because it damages the landscape. It’s not a question of landscape, it’s a question of the survival of humankind.

20 years ago, there were no companies you could invest in that were really clean. It’s different today. Even the dirtiest companies are now changing to be more efficient, cleaner. And sometimes they are doing it because they want to leave a better world for their children, but often they simply understand that if they don’t, they will disappear. They won’t be in business anymore in five or ten years.

Today, these new technologies are profitable, trendy, sexy even. People don’t show their guests their swimming pools anymore, they show their heat pumps or solar panels. They’re much more exciting!

1,404 solutions is a great achievement. What’s next for you? Do you want to scale up to 10,000 or do you have a new project in mind?

We’ll continue to select new solutions, new ideas are coming in regularly. There’s no goal in terms of numbers, we just take the best ones. Then we work to implement them. Today for instance, we are suggesting 50 legal recommendations to the new French parliament in order to push the 50 best French solutions onto the market.

This is quite technical though, and I’m sure you were wanting something more spectacular, so let me also tell you about something more spectacular. I want to fly with a hydrogen airplane, and I’m planning on flying around the world in a 150-metre, totally solar, totally clean solar zeppelin. It will be an epic journey, speaking to schools, universities, governments, big corporations and spreading the message of how important it is to explore new ways to thinking and acting to protect the environment.

With respect to cars, we have made great progress. However, in aviation there still seems to be a long way to go. Are you optimistic that the transformation will also speed up there?

It is more difficult in aviation. It’s much more difficult to replace jet fuel with batteries because the batteries weigh between 15 and 30 times more than the kerosene they need to replace. This makes it difficult, but let’s be clear, aviation only accounts for 2.5% of global CO2 emissions. So we shouldn’t focus solely on attacking aviation and forget to do the other things we have to do. Textiles are 7%, cars 15%, construction and living in buildings is 40%. There is a big margin to be better everywhere.

Airbus is working on a hydrogen airplane for 2035, and I’m sure they will succeed because they’re a brilliant company. But even today, aviation could be 20% better. You need to have a constant descend approach, more direct routes, an electric feeder at the airport allowing to cut the auxiliary power unit that runs all the time. There are many things that could be done today, but it’s difficult to achieve it. Air traffic controls don’t want to change their habits, their procedures, and that’s how it is everywhere. Maybe it’s more technological for aviation, but even here, much of it is about changing mindsets and old habits.

Despite all the advancements in technology, we are still losing time. How can we make sustainable transformation happen? Where’s the leverage?

In the past, solutions did not exist. Then the first solutions came, but they were too expensive. What I have proven with the Solar Impulse foundation is that there are more than 1,000 solutions available today, both ecological and profitable. And I thought that would be enough. But what needs to change is the fact that legal frameworks are based on old infrastructure. So you’re allowed to pollute, to pump as much CO2 as you want into the atmosphere. Many people will tell you, ‘well, you accuse me of polluting, but I respect the norms, I respect the law, what I do is legal’. This has to change. We need incentives in our regulations, but we also need to rewrite regulations that prevent new systems from coming onto the market. In public procurement for example, many countries do not allow new, innovative systems because they do not know the systems, it disrupts everyone’s habits, so instead they use established technologies that are old and inefficient.

We also need to start taking the overall cost of ownership into consideration instead of just the upfront investment. When you buy a diesel bus or build a badly-constructed house, of course it’s cheaper to start with. But over time, the polluting system is more expensive than an electric bus or a well-insulated house. The clean and efficient system will amortise the upfront investment. This is a mindset change we need to establish in public and private procurement, in everyone who works with infrastructure. If we don’t, we will be locked into old infrastructure for 50 more years instead of having efficient infrastructure that saves us resources and money.

So legal frameworks need to change. Where do you see Europe in this context compared to Asia or North America?

In North America, it’s a highly political topic. This makes it very difficult because everything becomes dogmatic. If you believe in climate change or protecting the environment, you’re a democrat. If you don’t, you’re a republican. The problem is that science goes far beyond political parties. In Europe on the other hand, you have the European commission with people who are not elected directly by the population. In other words, European commissioners are much freer to introduce ambitious reforms. And some of these reforms are quite interesting, the green deal for example. The green deal uses economic recovery to push new technologies, clean technologies. It’s not perfect, I know, but they are doing quite a good job of changing old habits.

You’re a father of three daughters. What do you think the world will look like for them in 20, 30 years?

There are several scenarios. Either we won’t change enough and end up with a miserable quality of life. Miserable. With heat waves, droughts, floods, with tropical disease in Europe and natural catastrophes. With millions, hundreds of millions of climate refugees. It really could turn into a nightmare.

Or we will do what we have to do, not tomorrow but today, we will become efficient, commit to a circular economy, to renewable energies and stop wasting everything. And if we do that, we will limit the damage. I don’t think we can do better than a temperature increase of 1.5 degrees, but such an increase, while not good, will not destroy life on earth. And that is what we have to aim for.

I’m not sure which scenario we are going to choose. The gap between what we are doing and what we should be doing is growing every day. If we carry on like now, it will be a disaster. If we do implement the solutions though, our children will have a reasonably good quality of life.

Changing mindsets can be very difficult, especially because the task seems so big. Do you think everyone can be part of the solution?

Absolutely, at every level. Heating your building to 20 degrees instead of 25 in winter is healthier, it saves 40% of your energy bill and 40% of the CO2 emissions. We need a change of mindset but in a positive way. We are not asking people to make sacrifices. We are not asking people to compromise on their comfort, on their quality of life, no, we are showing them that they can have a better quality of life, they can do better, they can have better purchasing power because they’re going to save money and protect the environment at the same time. It’s a fantastic vision to share with them. We have to show them that there’s so much incentive to do it. So for me, it’s an exciting prospect, it’s truly exciting, it’s not threatening at all. And it’s logical. It’s all so logical, we just have to do it because it’s common sense.

If a fairy godmother were to grant you a wish, what would that wish be?

If it’s a really good fairy, I would ask her to make humans wiser. That would be really good. If it’s a fairy that cannot accomplish miracles, I would ask her to push politicians to modernise the standards, the norms, the requirements of our legal frameworks in order to create a need to pull solutions to the market. Innovation often needs to be pushed, we push it with grants, incubators, pitches. But there also needs to be a legal need to use them. If we had regulation with new standards, new norms that create the need to be cleaner and more efficient, what would happen? It would automatically pull all these innovations onto the market and make them accessible to everyone. That is a reasonable wish I can make.